About the invention and introduction of the Pickelhaube in Prussia

by Sandy Michael Heinemann

Much has been written about the invention and introduction of the “Pickelhaube”, about the reason for its spike and the origin of the nickname of the helmet, simply designated “helmet” or “leather helmet” in official German, but the narrative is still today unfortunately quite vague. What is known about it was mostly published in different editions of the "Zeitschrift für Heereskunde", a German scientific magazine for military history. Unfortunately, these publications still have large gaps. For example, it could never be clarified to whom the idea of the helmet was going back. Thus remained space for speculation and rumors, which is why I wanted to find more original sources with which the considerable knowledge gaps around the invention of the „Pickelhaube“ could be closed a little further. I really found these sources in newspaper articles from different daily- and specialist-newspapers from the middle of the 19th century, which luckily contained very detailed information on this topic. The newspaper articles extend the previous research results with a few new informations about the invention history of the spiked helmet.

The nickname "Pickelhaube" was quickly established in Germany for the new helmet, which was introduced to the Prussian army in 1842. This popular name came already up in an article dated July 22, 1841, as the newspaper „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung No. 63/1841“ wrote about the helmet: "They are similar to the Pickelhaubes from the days of knights."; and further: "What is peculiar about these new helmets in the medieval form is that they have a conical spike at the top...".1 In later newspaper articles, the design of the spiked helmet was also compared to the "medieval headgear of foot soldiers" or to the "balaclavas of German Landsknechts". It is therefore worth emphasizing the fact that the word „Pickel“ in the German nickname did not allude to the spike on the helmet, but the name „Pickelhaube“ was a dialect for the medieval "Kettle-hat" (in German "Beckenhaube"). Most likely, the German nickname was a deliberate play on words.

Fig. 1 shows a Landsknecht with a helmet in a similar shape to the early Pickelhaube. Compared to Fig. 2, it‘s guessable how these comparisons came to the mind of the journalists.

The stately appearance of a soldier was more important at the time than it is today, that’s why the topic was touched on in almost all newspaper reports that I came across for researching this article. In general, the opinion about the design of the Pickelhaube was divided first2, but later it was considered to be functional and stylish.3 The soldiers and military personnel around the world quickly learned to appreciate the advantages of the helmet, and so it was gradually introduced into many armies around the world.4

As well known, the shako has been usually worn in the Prussian army before the spiked helmet was introduced. Although this headgear was dressy, it offered hardly any protection to the soldiers and the felt soaked up with water when it rained, which made it very uncomfortable to wear.5

Therefore, at the beginning of the reign of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV., consideration was given to introduce new uniforms that focused more on performance and health of the soldiers than on appearance.6 Another reason was certainly that the Napoleonic Wars were not that long ago and people were still afraid of another attack by France. Some newspaper articles between 1840/1841 testifies some nervousness in this regard.

That’s why in mid-May 1841, two commissions for the “examination and revision of the assembly and armament system” were set up by royal cabinet order. The 1st commission was responsible for clothing and equipment, headed by a Lieutenant General von Rohr from Breslau. The 2nd commission, responsible for organizational and formation matters, was headed by Prince Friedrich of Prussia (1794-1863), the nephew of King Friedrich Wilhelm III., who died in 1840. Other members were: General von Natzmer, General von Nostitz, Graf von der Gröben, Graf von Barner, Graf von Tümpling, Colonel von Erhardt (artillery), Colonel von Schack (5th Hussar Regiment), Major von Döring (from the War Ministry) , Major Graf von Waldersee (Commander of the Training Infantry Battalion) and the Secret War Councilor Schnobitz.6

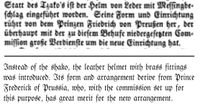

The results of these commissions included the tunic (Waffenrock), a new packing system and the spiked helmet. Last, however, was invented by Prince Friedrich of Prussia, proven by a large number of newspaper articles in which it has been written that the idea and construction of the Pickelhaube can be traced back to him. For example, the Illustrated Newspaper, issue No. 37 from March 1844, wrote:

Furthermore, according to the „Allgemeine-Militärzeitung“ No. 46/1841 he sent a self-designed infantry helmet to Berlin for presentation some time before the start of the commissions, which received a great deal of recognition there.6 He was going on to develop the helmet further between 1840/42 with Mr. Wilhelm Jäger from the „Metal-goods Factory Wilhelm Jäger“ in Elberfeld.7 Under his management and with a lot of his own money the Jäger-Company was able to offer the War Ministry metal helmets for 6 Thaler and 25 Groschen (see also Fig. 4 and Fig. 5)8, just two months after the commission started, in June 1841. The enlisted men of the Garde du Corps-Regiment were already dressed in these for testing it in July 1841.9

The suitability of the helmets was not only tested on the basis of such wearing tests, which took place in every conceivable situation and in all weathers, but stationary tests also took place. With these, the helmets were filled with straw heads and placed on man-high wooden posts. Next, strong soldiers of the Garde du Corps slashed at them with their sabers. The spike on the helmet proved particularly advantageous here, as it deflected the saber strikes and the helmet stayed in place.9 The previous cuirassier helmets with the crest did not survive these tests so well. The crest also ensured a high center of gravity, making the helmet was very susceptible to wind.10

The spike was probably also adapted for the leather infantry helmet due to the excellent results in the stationary test series with the saber strikes. However, because the prince sent an "infantry helmet" to Berlin6, it may be just as well be that he also suggested a spiked helmet of leather for the infantry from the start. However, that is only speculation.

Although the commission was in favor of the new uniform, the War Ministry initially wanted to decide against it, due to the high costs. They also had old uniforms in stock for around 400,000 marks (or for about 500.000 soldiers), which they still wanted to use up.11 This didn’t change as during a maneuver in Silesia in 1841 several young soldiers struggled or collapsed because of the poor equipment. And also not when a Major named „von Menschwitz“ succeeded in halving the cost of 900,000 Reichstaler for the introduction of the Pickelhaubes.12 But may be that were reasons why in August/September 1842, at the major maneuver in Euskirchen, the 1st Battalion of the 15th Infantry Regiment was employed with the new uniforms including the new infantry-helmets from Jäger company, for a major practical test. There, the new uniform and the spiked helmets were completely convincing13, which led to a change in royal opinion, and the king ordered to introduce the new uniform with the Pickelhauben into the Prussian army on October 23rd, 1842.4

Due to the success of the maneuver in Euskirchen, the decision was also made to equip all infantry regiments with the smooth leather helmets made by the Jäger-Company.7 So, contrary to claims that they produced metal goods only, the Jäger-Company produced spiked leather helmets in larger quantities as earlier as 1842.7; 13 This is again confirmed by an English article from a British military journalist, who was present at the autumn maneuvers in 1842 (Fig. 6). He also describes that the 1st Battalion of Infantry Regiment No. 15 wore the new uniform with the leather helmets conceived by Prince Frederick of Prussia and that Wilhelm Jäger from Elberfeld produced these high quality leather helmets for 11 Schillings.14

The tests for the cuirassier helmets were particularly thorough9, so the cuirassiers did not receive the A.K.O. for the new helmets, which were also produced by the Jäger-Company, before February 22, 1843.15

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find the cabinet order for the infantry-helmets, but I found the article shown in Fig. 7 about the competitor Harkort (Christian Harkort from Harkorten, Westph.), from whom it was sometimes assumed that he has invented and produced the first spiked helmets.13 In this article it was written that the buffalo leather helmets of Harkort were not as durable as the smooth leather helmets from the Jäger-Company and therefore rejected by the War Ministry for majority use. Harkorts helmets were only found to be good for the dragoon regiments, for which he received an A.K.O on November 29, 1842.7

According to the same article of the Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung No. 9/1843, helmet samples of all branches of arms were also sent to the London War Office, but unfortunately, I was unable to check this (Author's note: Maybe there is still unseen archive material about the invention of the spiked helmet there?).

In any case, the unconfirmed legends that King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. of Prussia saw the Pickelhaube in Russia first or that he commissioned the military painter Hermann Stilke (1803-1863) to design a helmet16 should be obsolete, due to that large number of articles with Prince Friedrich of Prussia as the inventor of the spiked helmet.6 As far as I could research, these rumors were not published until 1918 in the magazine "Archiv für Waffen- und Uniformkunde" No. 2/3, but the author "F. Rascher” from Frankfurt am Main guilty of evidence for these allegations.16

The Pickelhaube was an important and well-thought-out military innovation, which had the improvement of the endurance and protection of the soldier in mind, in combat or against the weather. The helmet was made of light hardened leather, was lacquered, comfortable to wear and, thanks to its shape, had a firm fit. Further, it could defy any weather. The front visor was pulled down to the level of the eyebrows, which should prevent the soldier from being blinded by the sun and also from dripping rainwater into his eyes. Similar reasons for the neck guard, which was pulled down a long way to deflect saber strikes and also prevent rainwater from dripping into the neck. A brass cross fitting was screwed onto the helmet, with light but robust arms which were intended to deflect the cavalrymen's saber strikes from above. Besides a base for the screw-on spike, the cross fitting was provided with holes for ventilating the head to protect it from overheating. In general, all brass applications should not only look chic but also strengthen the helmet with great lightness to protect the head against saber strikes of the cavalry from all sides.5 At the front, this protection was provided by the magnificent eagle plate and the brass visor trim on the front visor. At the back, this was provided by the neck rail, and on the sides by the with brass plates covered chinstrap, the so-called chinscale. With a closed chinstrap, the helmet, which was already well-adapted, would also sit firmly on the head when it was in motion or if hit by a saber.5 A large number of the requirements for a helmet just listed are also confirmed in the report by the Garde du Corps, which was drawn up for the test helmet of the W. Jäger company in 1841 (see again the transcripts Fig. 4 + 5).8 The rest of the desired properties of a soldier's helmet that I have listed come from articles in specialist journals of the time.5

At parades, many regiments always wore splendid bushes of hair or feathers on their headgear, which shouldn’t be missed also on the new helmet. For this reason, the spiked helmets were provided with a screw-off brass spike that could be replaced by a hair plume funnel. The brass spike was worn for normal duties, the funnel was screwed on, by regiments authorized to do so, for parades.4 Perhaps this could also be the reason for the spike, as tradition and appearance had a higher priority than today. Maybe they wanted to attach a bush of hair and surely to ventilate the helmet, as this topic was often touched on at that time.5 Due to the reason that a hair plume funnel was only worn on parades, they had to find an alternative for normal duties, because without a hair plume or spike the helmet would not look pleased.

So there was hardly anything that wasn't thought out about this helmet. At that time it was probably the most advanced military helmet. However, weapon technology changed and protection against saber strikes became obsolete. The fashion taste also changed, but the Pickelhaube has got some very positive adjustments for my taste (Fig. 8).

It became an all-German landmark and despite the later no longer existing protection against modern weapons it has been worn with pride until the end of the German Empire.4

(Bassum, 2021-03-26 / revised on 2022-01-29)

Sources (All sources are in German) :

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 63/1841, Seite 503, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Allgemeine Zeitung“ Nr. 348/1842, Seite 2780, Artikel: Die Uniform - Bemerkungen über die gegenwärtige Reform in der Bekleidung der Heere

- „Illustrierte Zeitung“ Nr. 37/1844(2), Seite 166, Artikel: Die neue Uniform und die großen Manöver in Preußen

- „Aus der Frühzeit der Pickelhaube“ (Zeitschrift für Heereskunde Nr. 124/1943, Autor: Herbert Knötel)

- „Preußische Wehrzeitung“ vom 11.9.1853, Artikel: Pickelhaube und Krempenhut

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 46/1841, Artikel: Preussen vom 24.5.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 9/1843, Seite 71, Artikel: Preussen vom 28.12.1842

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 166, Heft 6 von 1959 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 3

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 169, Heft 3 von 1960 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 4

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 164, Heft 3 von 1959 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 2

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung Nr. 61/1841, Seite 483, Artikel: Preussen vom 7.7.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 83/1841, Seite 660, Artikel: Preussen vom 27.9.1841

- Westfalen.Museum-Digital.de - Stadtmuseum Hagen / Sammlung: [Hagener Stücke] / Pickelhaube

- „The United Service Magazine and Naval and Military Journal“, Part 3, Pages 514-520

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 175, Heft 3 von 1961 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 5

- „Archiv für Waffen- und Uniformkunde“, Heft 2/3 1918 - Die preußischen Infanteriehelme“

Add. to #1 - Further sources about the origin of the name „Pickelhaube“:

- „Regensburger Zeitung“ Nr. 182/1841(2), Seite 7, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Aus der Frühzeit der Pickelhaube“ (Zeitschrift für Heereskunde Nr. 124/1943, Autor: Herbert Knötel)

- „Archiv für Waffen- und Uniformkunde“, Heft 2/3 1918 - Die preußischen Infanteriehelme“

- „Neue Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 28/1858, Seite 217, Artikel: Einige Bemerkungen über d. Bekleidung d. preuß. Infanterie

- „Münchener Politische Zeitung“ Nr. 185/1841, Seite 991, Artikel: Preussen, vom 27.7.1841

- „Bayreuther Zeitung“ Nr. 239/1842, Seite 954, Artikel: Aus dem Lager bei Euskirchen vom 30.9.1842

- „Universal-Lexikon d. Gegenwart & Vergangenheit o. neuestes encyclopädisches Wörterbuch d. Wissenschaften, Künste & Gewerbe: Trommel - Vergrösserungswörter“ Band 32 von 1846, Seite 278

Add. to #2 - Further sources with sceptical comments about the look of the Pickelhaube:

- „Nürnberger Kurier (Friedens- & Kriegs-Kurier)“ Nr. 265/1843 (169. Jahrgang), Artikel: Berlin vom 18.9.1843

- „Fürther Tageblatt“ Nr. 67/1850, Seite 311, Artikel: - Wenn es auch nicht gelingen sollte…

Add. to #3- Further sources with positive comments about the look of the Pickelhaube:

- „Preußische Wehrzeitung“ vom 11.9.1853, Artikel: Pickelhaube und Krempenhut

- „Neue Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 28/1858, Seite 217, Artikel: Einige Bemerkungen über d. Bekleidung d. preuß. Infanterie

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 46/1841, Artikel: Preussen vom 24.5.1841

- „Didaskalia“ vom 28.12.1842, Artikel: Das Lager bei Grimlinghausen

Add. to #4 - Further infos about the Pickelhaube in foreign armies:

- „Regensburger Zeitung“ Nr. 182/1841(2), Seite 7, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Universal-Lexikon d. Gegenwart & Vergangenheit o. neuestes encyclopädisches Wörterbuch d. Wissenschaften, Künste & Gewerbe: Trommel - Vergrösserungswörter“ Band 32 von 1846, Seite 278

- „Archiv für Waffen- und Uniformkunde“, Heft 2/3 1918 - Die preußischen Infanteriehelme“

Add. to #5- Further sources about requirements for military helmets around 1840 and disadvantages of felt hats in rain:

- „Archiv für Waffen- und Uniformkunde“, Heft 2/3 1918 - Die preußischen Infanteriehelm

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung Nr. 61/1841, Seite 483, Artikel: Preussen vom 7.7.1841

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 164, Heft 3 von 1959 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 2

- „Neue Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 28/1858, Seite 217, Artikel: Einige Bemerkungen über d. Bekleidung d. preuß. Infanterie

Add. to #6 - Further sources that prove that the performance and health of the soldiers focused in the development of the new helmet:

- „Zeitschrift für Heereskunde“ Nr. 164, Heft 3 von 1959 - Die Bekleidung & Ausrüstung der preuß. Kürassiere von 1809-1918 - Teil 2

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 69/1840, Seite 547, Artikel: Berlin vom 9.8.1840

- „Neue Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 28/1858, Seite 217, Artikel: Einige Bemerkungen über d. Bekleidung d. preuß. Infanterie

- „Illustrierte Zeitung“ Nr. 37/1844(2), Seite 166, Artikel: Die neue Uniform und die großen Manöver in Preußen

Add. to #7 - Further sources that 2 commissions have been initiated to improve uniforms and about wearing tests of the IR15 at the maneuver in Euskirchen::

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 40/1841, Seite 316, Artikel: Preussen vom 2.5.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung Nr. 61/1841, Seite 483, Artikel: Preussen vom 7.7.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 83/1841, Seite 660, Artikel: Preussen vom 27.9.1841

- „Fränkischer Merkur“ Nr. 180/1841, Seite 71, Artikel: Preußen vom 13.6.1841

- „Illustrierte Zeitung“ Nr. 37/1844(2), Seite 166, Artikel: Die neue Uniform und die großen Manöver in Preußen

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 9/1843, Seite 71, Artikel: Preussen vom 28.12.1842

- „Didaskalia“ vom 28.12.1842, Artikel: Das Lager bei Grimlinghausen

- „Das Königsmanöver im Jahre 1842 – Ein Helm erzählt seine Geschichte“ (Zeitschrift für Heereskunde Nr. 456/2015, Autor: Ulrich Schiers)

- „Das königlich preussische 15. Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Friedrich der Niederlande … in den Kriegsjahren 1813, 14 und 15“, Seite 172

Add. to #8 - Further sources which named Prince Prinz Friedrich von Preussen as the originator of the Pickelhaube:

- „Daheim: ein deutsches Familienblatt und Illustrationen“, Band 26 (1890), page 503

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 63/1841, Seite 503, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 46/1841, Artikel: Preussen vom 24.5.1841

- „Regensburger Zeitung“ Nr. 182/1841(2), Seite 7, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Münchener Politische Zeitung“ Nr. 185/1841, Seite 991, Artikel: Preussen, vom 27.7.1841

- „Illustrierte Zeitung“ Nr. 37/1844(2), Seite 166, Artikel: Die neue Uniform und die großen Manöver in Preußen

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 9/1843, Seite 71, Artikel: Preussen vom 28.12.1842

- „Didaskalia“ vom 28.12.1842, Artikel: Das Lager bei Grimlinghausen

- „Fränkischer Merkur“ Nr. 180/1841, Seite 71, Artikel: Preußen vom 13.6.1841

Add. to #9 - Further sources about wearing tests of the Garde du Corps with the Pickelhaube:

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 63/1841, Seite 503, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Regensburger Zeitung“ Nr. 182/1841(2), Seite 7, Artikel: Preussen vom 22.7.1841

- „Fränkischer Merkur“ Nr. 180/1841, Seite 71, Artikel: Preußen vom 13.6.1841

Add. to #11 - Further sources that the introduction of the new uniform was delayed due to large amounts of stored uniforms:

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 46/1841, Artikel: Preussen vom 24.5.1841

- „Allgemeine Militär-Zeitung“ Nr. 67/1841, Seite 531, Artikel: Preussen vom 26.7.1841